So, you might know TheTimeChamber is interested in all things Cold War. We have read a lot of books and articles on the subject, and been to lots of museums and sites. This story is one that fascinates us the most though. Most people think that the closest we have come to Nuclear armageddon was the Cuban Misile Crisis in the 1960’s. That however is not quite correct and we in fact came a lot closer in the 1980s, when Soviet paranoia was at its highest. Its only thanks to the smart thinking of a Soviet Intelligence Officer, and 2 spies from opposing sides prepared to risk their lives that disaster was averted…

Read the full story, taken from the Daily Mail:

Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant-colonel in the military intelligence section of the Soviet Union’s secret service, reluctantly eased himself into the commander’s seat in the underground early warning bunker south of Moscow.

It should have been his night off but another officer had gone sick and he had been summoned at the last minute.

Before him were screens showing photographs of underground missile silos in the Midwest prairies of America, relayed from spy satellites in the sky.

He and his men watched and listened on headphones for any sign of movement – anything unusual that might suggest the U.S. was launching a nuclear attack.

Stanislav Petrov may have prevented all out nuclear war between the U.S. and the USSR. This was the height of the Cold War between the USSR and the U.S. Both sides packed a formidable punch – hundreds of rockets and thousands of nuclear warheads capable of reducing the other to rubble. It was a game of nerves, of bluff and counterbluff. Who would fire first? Would the other have the chance to retaliate?

The flying time of an inter-continental ballistic missile, from the U.S. to the USSR, and vice-versa, was around 12 minutes. If the Cold War were ever to go ‘hot’, seconds could make the difference between life and death. Everything would hinge on snap decisions. For now, though, as far as Petrov was concerned, more hinged on just getting through another boring night in which nothing ever happened.

Except then, suddenly, it did. A warning light flashed up, screaming red letters on a white background – ‘LAUNCH. LAUNCH’. Deafening sirens wailed. The computer was telling him that the U.S. had just gone to war.

The blood drained from his face. He broke out in a cold sweat. But he kept his nerve. The computer had detected missiles being fired but the hazy screens were showing nothing untoward at all, no tell-tale flash of an missile roaring out of its silo into the sky. Could this be a computer glitch rather than Armageddon?

Instead of calling an alert that within minutes would have had Soviet missiles launched in a retaliatory strike, Petrov decided to wait.

The warning light flashed again – a second missile was, apparently, in the air. And then a third. Now the computer had stepped up the warning: ‘Missile attack imminent!’

But this did not make sense. The computer had supposedly detected three, no, now it was four, and then five rockets, but the numbers were still peculiarly small. It was a basic tenet of Cold War strategy that, if one side ever did make a preemptive strike, it would do so with a mass launch, an overwhelming force, not this dribble.

Petrov stuck to his common-sense reasoning. This had to be a mistake. What if it wasn’t? What if the holocaust the world had feared ever since the first nuclear bombs dropped on Japan in 1945, was actually happening before his very eyes – and he was doing nothing about it?

He would soon know. For the next ten minutes, Petrov sweated, counting down the missile time to Moscow. But there was no bright flash, no explosion 150 times greater than Hiroshima. Instead, the sirens stopped blaring and the warning lights went off.

The alert on September 26th, 1983 had been a false one. Later, it was discovered that what the satellite’s sensors had picked up and interpreted as missiles in flight was nothing more than high-altitude clouds.

Petrov’s cool head had saved the world.

He got little thanks. He was relieved of his duties, sidelined, then quietly pensioned off. His experience that night was an extreme embarrassment to the Soviet Union.

Petrov may have prevented allout nuclear war but at the cost of exposing the inadequacies of Moscow’s much vaunted earlywarning shield.

Instead of feeling relieved, his masters in the Kremlin were more afraid than ever. They sank into a state of paranoia, fearful that in Washington, Ronald Reagan was planning a first-strike that would wipe them off the face of the earth.

The year was 1983 and – as a history documentary in a primetime slot on Channel 4 next weekend vividly shows – the next six weeks would be the most dangerous the world has ever experienced.

That the U. S. and the Soviet Union had been on the brink of world war in 1962, when John Kennedy and Nikita Krushchev went head-to-head over missiles in Cuba, is well known. Those events were played out in public. The 1983 crisis went on behind closed doors, in a world of spies and secrets.

A quarter of a century later, the gnarled old veterans of the KGB, the Soviet Union’s secret service, and their smoother counterparts from the CIA, the U.S. equivalent, have come out from the shadows to reveal the full story of what happened. And a chilling one it is. From their different perspectives, they knew the seriousness of the situation.

‘We were ready for the Third World War,’ said Captain Viktor Tkachenko, who commanded a Soviet missile base at the time. ‘If the U.S. started it.’

Robert Gates – then the CIA’s deputy director of intelligence, later its head and now defence secretary in George Bush’s government – recalled: ‘We may have been on the brink of war and not known it.’

That year, 1983, the rest of the world was getting on with its business, unaware of the disaster it could be facing.

Margaret Thatcher won a second term as Prime Minister but her heir-apparent, Cecil Parkinson, had to resign after admitting fathering his secretary’s love child. Two young firebrand socialists, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, were elected MPs for the first time.

Police were counting the dead bodies in serial killer Dennis Nilsen’s North London flat, the Brinks-Mat bandits got away with £25million in gold bullion and ‘Hitler’s diary’ was unearthed before being exposed as a forgery. England’s footballers failed to qualify for the European finals. The song everyone was humming was Sting’s Every Breath You Take – ‘Every breath you take, every move you make, I’ll be watching you.’ It was unwittingly appropriate as that was precisely what, on the international stage, the Russians and Americans were doing.

On both sides there were new, more powerful and more efficient machines to deliver destruction. The Soviets had rolled out their SS-20s, missiles on mobile launch pads, easy to hide and almost impossible to detect. Meanwhile, the Americans were moving Pershing II ballistic missiles into Western Europe, as a direct counter to a possible invasion by the armies of the Warsaw Pact (as the Soviet Union and its satellites behind the Iron Curtain were known).

They were also deploying ground-hugging cruise missiles, designed to get under radar defences without being detected. Then Reagan, successor at the White House to Jimmy Carter, upped the ante in a provocative speech in which he denounced the Soviet Union as ‘the Evil Empire’. His belligerence rattled the new Soviet leader, Yuri Andropov, a hardline communist and former head of the KGB whose naturally suspicious nature was made worse by serious illness. For much of the ensuing crisis he was in a hospital bed hooked to a dialysis machine.

His belief that Reagan was up to something was reinforced when the President announced the start of his ‘Star Wars’ project – a system costing trillions of dollars to defend the U.S. from enemy ICBMs ( Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles) by shooting them down in space before they re-entered earth’s atmosphere. He saw this as an entirely defensive measure, but to the Russians it was aggressive in intent. They saw it as a threat to destroy their weapons one by one and leave the USSR defenceless.

Even more convinced of Washington’s evil intentions, Andropov stepped up Operation RYAN, during which KGB agents around the world were instructed to send back any and every piece of information they could find that might add to the ‘evidence’ that the U.S. was planning a nuclear strike.

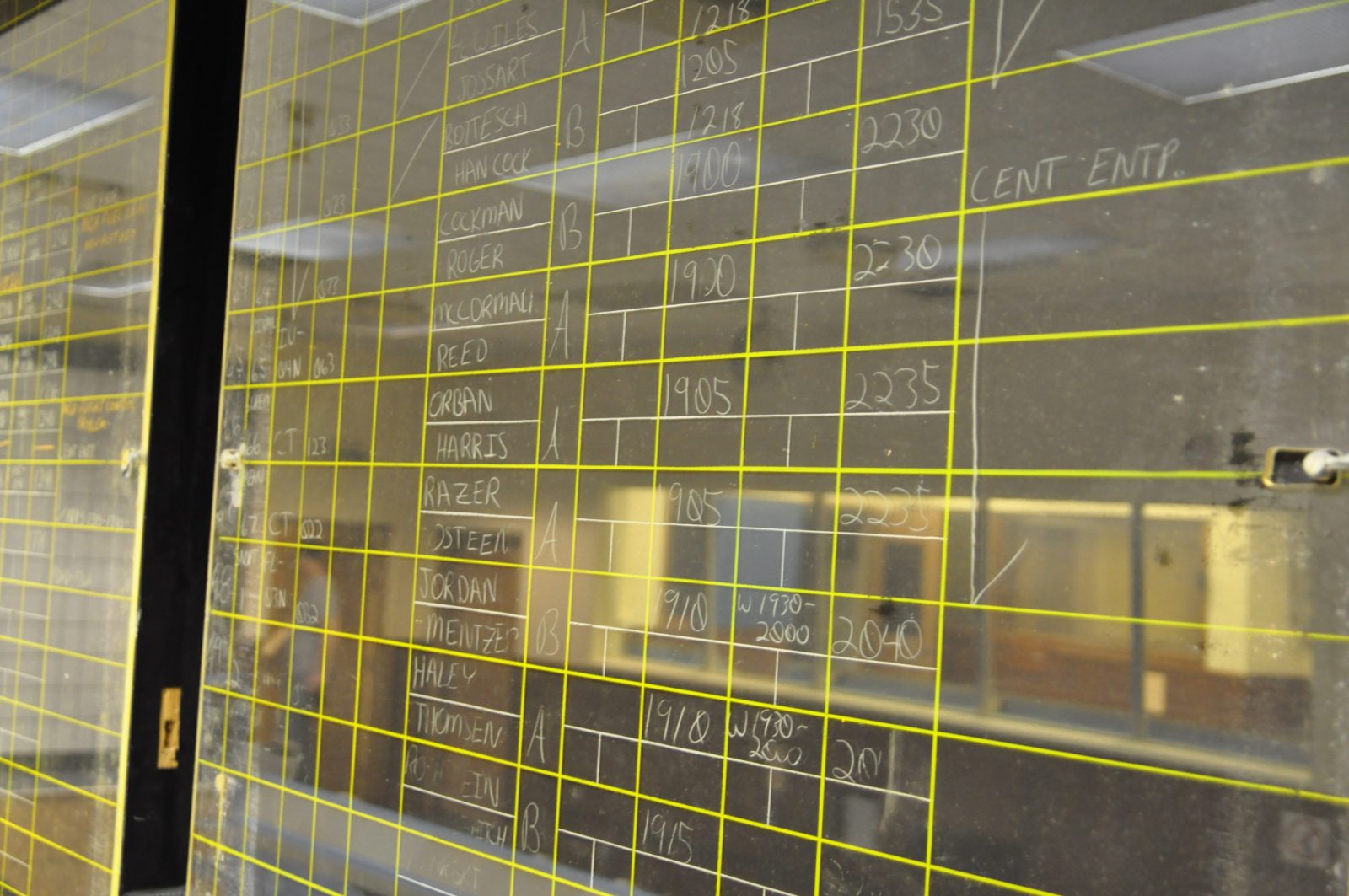

In the Soviet Union’s London embassy, Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB officer masquerading as a diplomat, was ordered to watch out for signs of the British secretly stockpiling food, petrol and blood plasma. In the KGB’s Lubyanka headquarters, every small detail was chalked up on a board, filling it with words until the mountain of ‘evidence’ appeared overwhelming. But the problem was, as a U.S. observer noted, that the KGB, while strong on gathering information, was hopeless in analysing it.

In reality, what it was compiling was the dodgiest of all dossiers, in which the ‘circle of intelligence’ remained a dangerously closed one. Not for the last time in matters of war, the foolhardiness of fitting facts to a preconceived agenda were exposed.

East-West tension increased when an unauthorised aircraft flew into Soviet air space in the Bering Sea, ignoring all radio communications. Su-14 intercept fighters were scrambled to shoot it down in the belief that it was a U.S. spy plane.

It turned out to be a civilian flight of Korean Airlines, KA-007, that had strayed off course en route from Alaska to Seoul. All 269 passengers and crew died. Reagan denounced the ‘evil Empire’ again, and Moscow detected once again the drumbeats of war.

AND THEN came the event that nearly triggered catastrophe. On November 2, 1983, Nato – the U.S.-led alliance of western forces – began a routine ten-day exercise codenamed Operation Able Archer to test its military communications in the event of war.

The ‘narrative’ of the exercise was a Soviet invasion with conventional weapons, which the West would be unable to stop. Its climax would be a simulated release of nuclear missiles. Command posts and nuclear bases were on full alert, but, as the Soviets were repeatedly told, no actual weapons were involved.

The words ‘EXERCISE ONLY’ screamed out from every message. But the Soviet leadership, with its eye on Reagan’s supposed recklessness, chose not to believe them. Andropov, in his sick bed, and his Kremlin advisers were gripped not just by current paranoias but by past ones. They were the World War II generation, forever conscious of how Hitler had fooled Stalin and launched his savage Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union in 1940 under the pretext of an exercise.

In the war that followed, 25million Soviet citizens died and the Motherland came close to caving in. To allow history to repeat itself would be unforgivable.

Now, the Kremlin watched and listened in horror as the West went though this drill. Top priority ‘flash telegrams’ went to Gordievsky and others in KGB stations around the world demanding ‘evidence’ that this exercise was a disguise for a real nuclear first-strike.

In Washington, the effect that Able Archer was having on the Soviet leadership was completely missed. In fact, rather than winding up for a war, Reagan was doing the opposite. At Camp David, the presidential retreat in Maryland, he had recently had a private screening of a made-fortelevision film called The Day After, which was a fictional reconstruction of the aftermath of nuclear war. The former Hollywood cowboy was more affected by this than by any military briefings he might have had. The film predicted 150 million dead. In his diary he wrote: ‘It left me greatly depressed. We have to do all we can to see there is never a nuclear war.’ The old war horse was changing course and soon he would begin to make overtures to Moscow that would lead to his first visit there, a building up of relationships and an easing of East-West tensions.

He very nearly did not get the chance. As Able Archer wound up to its climax, so too did the Kremlin’s paranoia. In the Nato exercise, Western forces were on the brink of firing a theoretical salvo of 350 nuclear missiles.

In the Soviet Union, the military went on to their equivalent of the U.S. defence forces’ DefCon 1, the final warning of an imminent attack and the last stage before pressing the button for an all to real massive retaliation.

On airfields, Soviet nuclear bomber pilots sat in their cockpits, engines turning, waiting for orders to fly. Three hundred ICBMs were prepared for firing and 75 mobile SS-20s hurriedly moved to hidden locations.

Surface ships of the Soviet navy dashed for cover, anchoring beneath cliffs in the Baltic, while its submarines with their arsenals of nuclear missiles slipped beneath the Arctic ice and cleared decks for action.

WHAT saved the situation were two spies, one on each side. Gordievsky, the KGB man in London, was really a double agent working for British Intelligence. He warned MI5 and the CIA that Able Archer had put Soviet leaders in a dangerous frame of mind.

It was the first inkling the West had had that the exercise was being viewed with such panic, and the Americans responded instantly by down-grading it. Reagan then made a very visible journey out of the country as a signal to the Soviets that he was otherwise engaged. Meanwhile, an East German spy, Topaz – real name Rainer Rupp – had infiltrated the Nato hierarchy at a high level and was privy to many of its secrets, was asked by Moscow urgently to confirm that the West was about to go to war.

Deeply embedded Topaz would know for sure, and all he had to do was dial a certain number on his telephone to confirm his master’s fears. His finger stayed off the buttons. His message back was that Nato was planning no such thing.

Moscow took a step back from the brink its own fevered imagination had created. At the same time, Able Archer reached its end, the simulation over, the personnel involved stood down. The date was November 11 – Armistice Day.

Only later did the West grasp how close the world had come to apocalypse. Reagan and his advisers were shocked, and more impetus was put behind finding ways to end the arms race with the Soviet Union.

The near-miss of 1983 has long been known by historians of the Cold War. But this documentary will bring it to a wider audience. Today, the West’s relations with post-communist Russia and its aggressive leader, Vladimir Putin, are strained. Bombers and spy planes nudge rival air space, testing nerves, just as they did in the early 1980s. The situation is ripe for misunderstandings. Those events, 24 years ago, are also a reminder that, for all the concerns about global warning, mankind’s greatest danger may still be its vast nuclear arsenals.

It has largely gone unnoticed that this year, with increasing fears of proliferation, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved its Doomsday Clock up to five minutes to midnight, closer to nuclear catastrophe than at almost any time since the phoney war of 1983.

See the original article in the Daily Mail here

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-505009/September-26th-1983-The-day-world-died.html#ixzz1sGxpJvfg